Thanks to The Dúchas project for the following Stories about Halloween from the Schools’ Collection. Dúchas is a project to digitize the Irish National Folklore Collection, one of the largest folklore collections in the world. The Schools’ Collection was originally to run from 1937 to 1938 but was extended to 1939 in specific cases. For the duration of the project, more than 50,000 schoolchildren from 5,000 schools in the 26 counties of the Irish Free State were enlisted to collect folklore in their home districts.

From the earliest recorded history in Ireland, Halloween (All Hallows Eve), or Oíche Shamhna was considered a turning point in the calendar. Samhain (November 1st), meant the start of winter, when cattle were brought down from summer pastures, tributes and rents paid, and other business contracted.

Samhain, marks the close of the season of light and the beginning of the dark half of the year and was therefore perceived as a liminal moment in time when movement between the otherworld and this world was possible.

“The fairies be out that night and they would take you away with them if you were out at that evil time. It is also said that the devil shakes his budges [fur] on the haws and turns them black and according to the old people if you eat a haw after Hallow Eve night you will have no luck” (Carndonagh, Donegal).

“It is said that the souls in Purgatory are released to visit their still mortal friends. Long ago the country folk before they retired to bed on this night always prepared a blazing fire and a well-swept hearth to welcome their unearthly visitors” (Manorhamilton, Leitrim).

Tales and legends of the returning dead, and the intrusion of supernatural beings into this world, were once plentiful. In his book Irish Folk Lore (1870), the writer ‘Lageniensis’ noted: ‘It is considered that, on All Hallows’ Eve, hobgoblins, evil spirits, and fairies, hold high revel, and that they are travelling abroad in great numbers. The dark and sullen Phooka [Púca] is then particularly mischievous and many mortals are abducted to fairy land. Those persons taken away to the raths are often seen at this time by their living friends, and usually accompanying a fairy cavalcade.’

The custom of dressing in grotesque costumes and making house visits to request small presents – fruit, sweets, and money – is traditionally dominant in the eastern half of Ireland.

“On Hallowe’en night the boys dress up like old men. Some of them dress up like old hags. They put on long trousers, women’s hats and soot on their faces and more of them have false faces. They go around from house to house and they are invited in and given something and the ringleader sings songs and plays tunes on the mouth organ and melodion. Then they get apples and nuts and sometimes money” (Clonshagh, Dublin).

A favourite form of activity for young people at this critical moment in time was to attempt to divine future events in a variety of different ways: would they become rich (or destitute), would they marry soon, and so on.

“They get three saucers and they put a ring in one saucer, clay in the other and water in the third. Then they put a cloth on some person’s eyes. If he puts his hand into the saucer with the ring in it he will be the first to be married. If he puts his hand into the saucer with the clay in it he will die soon. If he puts his hands into the saucer with the water in it he will cross the water to a foreign land” (Massbrook, Mayo).

In popular tradition, Hallowe’en is a time for feasting and merrymaking. For rural communities especially, the tasks of housing the livestock, harvesting and storing produce, picking and preserving fruits etc. should be completed by this time.

Feasting on fruits and rich foods represented an appropriate climax to the season. Festive

foods included colcannon, also known as stampy or pandy, sweet cake, fruits and nuts.

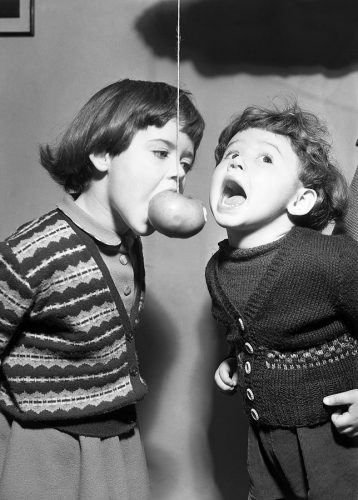

A variety of games were played, such as ‘dipping’ in a tub of water for coins, ‘snapping’ for apples and other amusements.

Another custom the people were fond of doing was to leave nine ivy leaves under a girl’s pillow at night and she was to say the following words:

“Those nine ivy leaves I place under my head to dream of the living and not of the dead

To dream of the man I am going to wed, and to see him tonight at the foot of my bed” (Tynagh, Galway)

“A bucket is put on the ground and each player goes around the bucket as quickly as possible ten times. Then he tries to catch, without falling, the apple hanging from the roof” (Killorglin, Kerry).

“We get a big basin of water and start to duck for apples. We get nuts and roast them in the fire. Then a knock comes to the door and the púca boys come in. They dance around the floor and sing songs” (Clongorey, Kildare)